Read Our Article in Cleveland Jewish News ↓

The Soviet Jewry Movement (circa 1963 to 1990) was a worldwide effort to obtain freedom for Jews in the Soviet Union, to practice their religion without state persecution or discrimination; or to emigrate to Israel, the United States or elsewhere to seek the blessings of freedom; and to pursue lives of their own choosing.

The Soviet Jewry Movement (circa 1963 to 1990) was a worldwide effort to obtain freedom for Jews in the Soviet Union, to practice their religion without state persecution or discrimination; or to emigrate to Israel, the United States or elsewhere to seek the blessings of freedom; and to pursue lives of their own choosing.

It was a small number of Beth Israel – The West Temple members who founded the committee that would grow into that worldwide movement. Don Bogart and Bob Steinberg, NASA engineers; David Gitlin, M.D.,; Herb Caron, a research psychologist at Case Western Reserve University; and Rabbi Daniel Litt were alarmed about Soviet-sponsored anti-Semitic acts, including executions of Jews for so-called “economic crimes.” Knowing that the U.S. Jewish community had failed to react to the escalating violence against Jews by the Nazis during the 1930s, these men vowed not to let it happen again. Taking their concerns to the well-known and respected Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver, who had recently returned from meetings with leaders in the Soviet Union, as well as the Cleveland Jewish Federation, they were told that this was no job for amateurs, and that they, the established leaders, had things in hand.

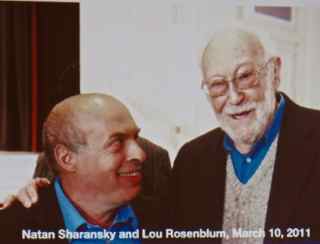

Undeterred, the West Siders began to strategize how to make the plight of Soviet Jews a topic of conversation at American dinner tables. They were soon joined by temple President Lou Rosenblum, who became the de facto leader of the group, while many temple members became active in various ways. Though they were never an official congregational committee, the temple did provide office space, and the group reported regularly to the Social Action Committee.

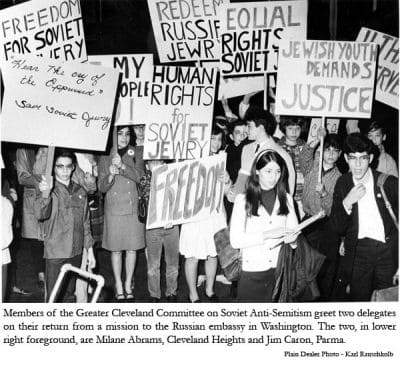

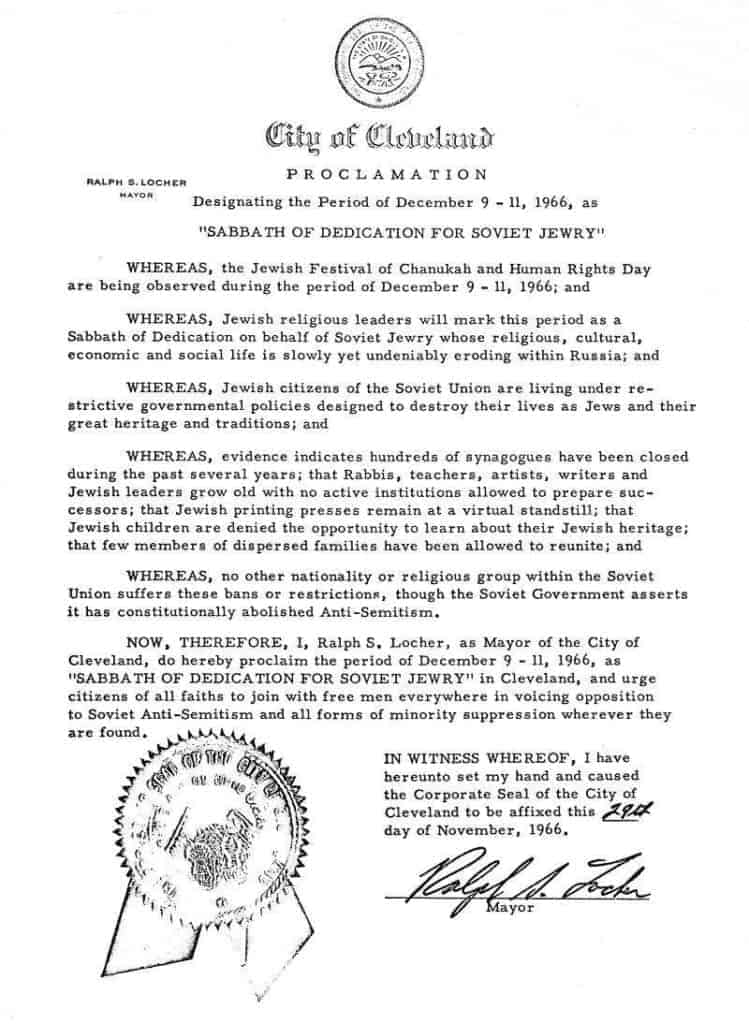

The group recruited prominent rabbis, ministers, and city officials, including Mayor Ralph Locher, who served as honorary chairman of the newly formed Cleveland Committee on Soviet Anti-Semitism. (The name was later changed to the Cleveland Council on Soviet Anti-Semitism as similar councils sprang up in other cities.)

They began by writing to public figures, including President John F. Kennedy, who, in 1963, announced that American wheat would be shipped to the USSR in response to their failed wheat harvest. “In the USSR, Jews are not permitted to make Passover matzah and should be allowed to use some of our American wheat for matzah,” they wrote Kennedy, according to Caron. Copies of the telegram were sent to major news outlets, who immediately picked up on the story, which achieved the first goal of making Americans aware of the situation in the Soviet Union.

The group undertook many other activities: meeting with American and Israeli dignitaries; producing a newsletter, slide show, radio program, editorials and ads for Cleveland newspapers, and a Handbook on Soviet Anti-Semitism to be used by other groups wishing to work for the cause. They supported the “refuseniks,” Jews who began applying to emigrate, by engaging thousands of Americans in sending them Jewish holiday cards, and by sponsoring personal contacts with American visitors, including youth groups.

Ultimately the movement that began with a small group of Beth Israel volunteers saw the fulfillment of its most ambitious goals, when, in the 1980s, Jews were finally allowed to emigrate in large numbers to America and Israel. As Herb Caron recalled in a 2013 commemoration, “It was an affirming experience for these Clevelanders to have helped produce a historic exodus, that was achieved almost without bloodshed.”

For a more complete, illustrated story of this remarkable group, with photos of its founders and others, see “Cleveland and the Freeing of Soviet Jewry,” on the Cleveland Jewish History website,https://www.clevelandjewishhistory.net/sj/