Vayishlach – Genesis 32:4 – 36:43 (Dec. 4/5)

As the Torah Turns

Rabbi Lader’s Weekly D’var Torah

Vayishlach – Genesis 32:4 – 36:43 (Dec. 4/5)

Our Torah portion this week is Vayishlach – Genesis 32:4 – 36:43 . Last week Jacob began his journey away from his family and the wrath of his brother Esau to make his way towards the unknown. He met God in his dream of the ladder, upon which the angels were moving up and down, and God promises Jacob that he will not be alone. Jacob awoke in the morning to move forward on his journey… and spent the next twenty or so years with his mother’s brother, Laban, and his family – falling in love with his daughter Rachel, working seven years to marry her, only to find out that it is her older sister, Leah, who was under the veil… and working another seven years for Rachel. Fathering 11 sons and one daughter with Rachel and Leah and their handmaidens, as well as building up Laban’s and his own wealth, Jacob is ready to return home and, with his wives and children and wealth, begins the journey home. Our portion begins as Jacob, hearing that Esau is coming his way with many horsemen, sets his wives and children and belongings on one side of a river… and he spends the night alone one the other side. Again, it is night… and again, Jacob could very well be afraid. And he struggles – wrestles – with an “ish” – a man… an angel… himself… God…? They struggle through the night, neither is victorious, and Jacob will not let his adversary go until he receives a blessing from him:

Then he said, “Let me go, for dawn is breaking.” But he answered, “I will not let you go, unless you bless me.” Said the other, “What is your name?” He replied, “Jacob.” Said he, “Your name shall no longer be Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with beings divine and human, and have prevailed.” Jacob asked, “Pray tell me your name.” But he said, “You must not ask my name!” And he took leave of him there. So Jacob named the place Peniel, meaning, “I have seen a divine being face to face, yet my life has been preserved.” The sun rose upon him as he passed Penuel, limping on his hip. (Gen. 32:27-32)

Aviva Zornberg, commenting on this portion in Genesis: A Living Conversation, notes that although he receives a new name, Jacob “…doesn’t quite lose the name Jacob. When Abram becomes Abraham, he’s no longer Abram. But Jacob always remains Jacob. He’s referred to as Jacob many more times than he’s referred to as Israel. He has two names from now on… His identity is complex. He’s constantly in struggle between the two sides of his identity. It’s not a transformation, but an evolution. Something has opened up in him, but it’s a resource, not something that will absolutely define him.” (p. 304) And what about us? How are we effected after a struggle? We might not receive a new name, but does the struggle effect our identity and create in us a new resource from which to draw as we make our way forward? Sometimes those struggles can effect us physically as well, and perhaps we “limp” as we forge ahead; but forge ahead we must.

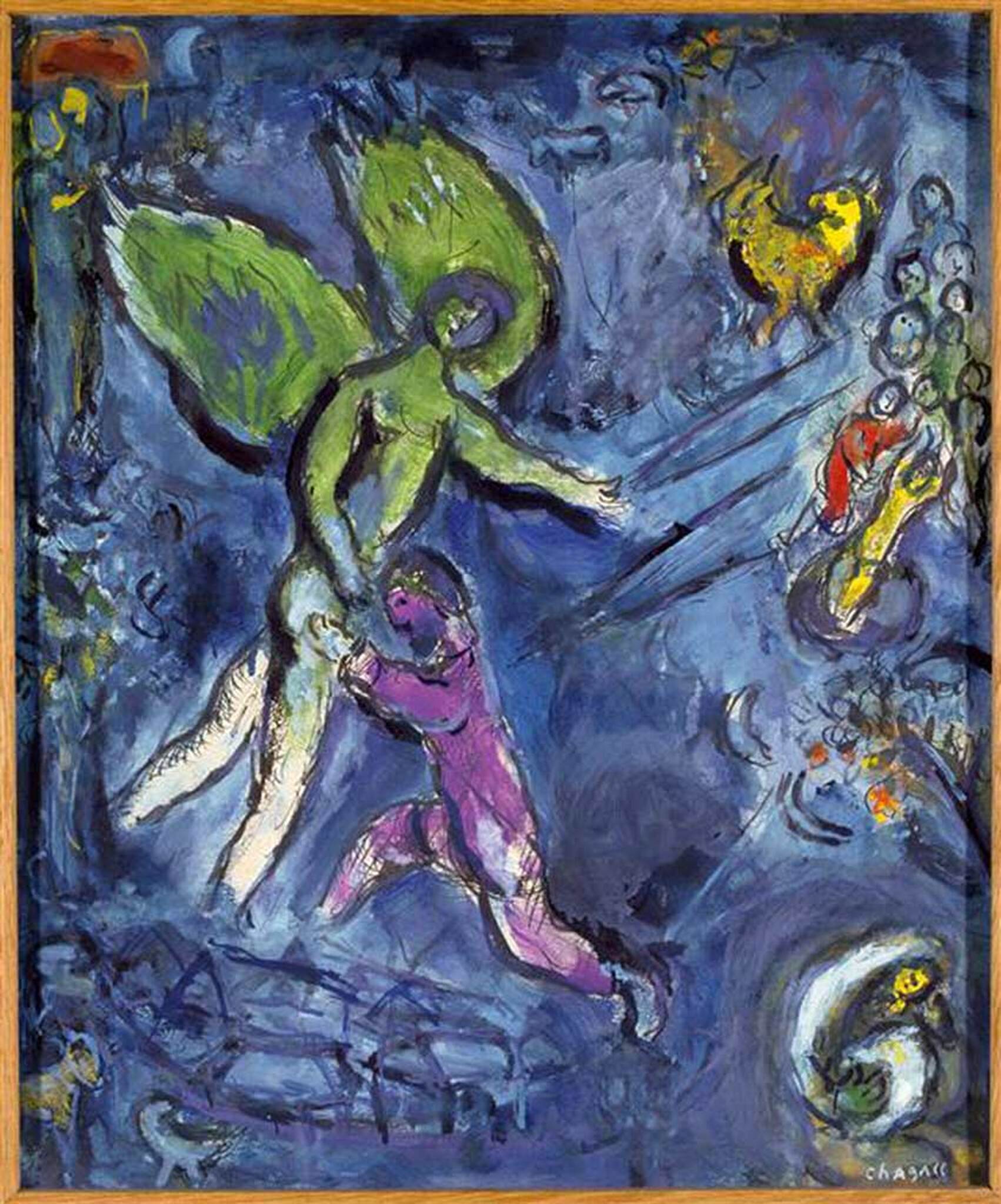

Nice: Marc Chagall Museum

“Jacob Wrestling With the Angel”

From the Marc Chagall Museum (36 Avenue Dr. Ménard). The museum houses the largest public collection of works by the Russian-French modernist artist Marc Chagall. The painting shown here — ”Jacob Wrestling With the Angel” — is one of Chagall’s ”Biblical Message” paintings that form the core of the museum’s collection. A few details on the work from its accompanying placard: Jacob Wrestling With the Angel – 1960-1966 – Oil on canvas This painting uses a deep purple in a continuation of the nocturnal atmosphere of Jacob’s Dream. Dawn will soon be breaking, and Jacob falls to his knees before the angel after a battle that has endured the night. The angel appears to be blessing Jacob as it touches his forehead. Pushed to the outer edges of the painting are various scenes from the patriarch’s life: in the upper left-hand corner is his encounter with Rachel at the well, while along the right-hand side, his son Joseph appears stripped by his brothers and thrown into a well. The sorrow of a father sobbing into the tunic of the son he believes to be gone is communicated through Jacob’s stooped position and prostration. Chagall generally uses this stance for the prophets announcing the misfortunes of the Jewish people.

[And what about the yellow rooster? In Chagall’s paintings it represents fertility, often painted together with lovers. Note that it is on the upper right side of the painting, across from Jacob and Rachel… and in front of the Joseph’s brothers.]

From Previous Weeks

Toledot – Gen. 25:19-28:9 (Nov. 20/21)

This is a story of parental love… and favorites… and birthrights and blessings.

Chayei Sarah – Genesis 23:1 – 25:18 (Nov. 13/14)

Why is a parsha about death called “life”?

Bereishit – Gen. 1:1-6:8 (Oct. 16/17)

Every soul consists of both a male and female persona…

Sukkot – Lev. 22:26-23:44

The Torah reading for Sukkot is Lev. 22:26-23:44, and includes the “fixed times of the Eternal, which you shall proclaim…